An acetabular fracture is a break in the socket portion of the hip’s ball-and-socket joint (the acetabulum). Unlike more common hip fractures that involve the femur, acetabular fractures affect the pelvic bone that connects with the femoral head.

These injuries are relatively uncommon but serious, often associated with high-energy trauma such as motor vehicle collisions. In older adults with osteoporosis, even a low-energy fall may cause an acetabular fracture.

Because the hip joint transmits large forces during movement, restoring the anatomy and smooth joint surface is essential to prevent long-term complications such as post-traumatic arthritis.

Anatomy and Biomechanics

The acetabulum is part of the pelvis, formed by the fusion of three bones: the ilium, ischium, and pubis. It forms the socket into which the femoral head fits, and both surfaces are lined with cartilage to allow smooth motion.

Around the acetabulum are several structural regions called columns and walls: the anterior column, posterior column, and quadrilateral plate along the inner surface. The hip joint is stabilized by surrounding ligaments, muscles, and soft tissues, while the sciatic nerve passes nearby and can be injured in some cases.

Because of the high loads transmitted through the hip, any irregularity or instability in the acetabular surface can lead to joint degeneration over time.

Etiology and Risk Factors

Mechanisms of Injury

High-energy trauma is the most common cause in younger patients, typically from motor vehicle or motorcycle collisions. The force may be transmitted through the femur, such as when the knee strikes the dashboard.

In older adults with weaker bones, acetabular fractures can occur from simple falls from standing height.

Risk Factors

– Advanced age and female sex, associated with osteoporosis

– Low bone density or metabolic bone disease

– Complex fracture patterns, including posterior wall involvement or marginal impaction

– Associated injuries such as nerve damage, femoral head dislocation, or soft tissue trauma

Classification and Patterns

The Judet-Letournel classification is most widely used for acetabular fractures. It divides fractures into elementary (simple) and associated (complex) types.

Common fracture types include:

– Posterior wall fracture

– Anterior wall fracture

– Posterior column fracture

– Anterior column fracture

– Transverse fracture

– T-shaped fracture

– Both-column fracture

Fractures involving the quadrilateral plate are frequent in elderly patients and often require special fixation techniques. The degree of displacement, comminution, and involvement of both columns influence the choice of treatment and long-term outcome.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms

Typical symptoms include severe hip or groin pain, inability to bear weight, and deformity such as shortening or rotation of the affected leg. Swelling and bruising are often present.

Associated Injuries

Because acetabular fractures usually result from high-energy trauma, other injuries are common, including:

– Pelvic or abdominal injuries

– Sciatic nerve injury, which may cause foot drop or sensory loss

– Internal bleeding from pelvic vessels

– Other skeletal injuries

Complications such as heterotopic ossification, avascular necrosis of the femoral head, and post-traumatic arthritis may develop during recovery.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Initial Assessment

Evaluation begins with trauma stabilization following ATLS principles. If pelvic instability or hemorrhage is suspected, temporary external fixation may be required.

Imaging

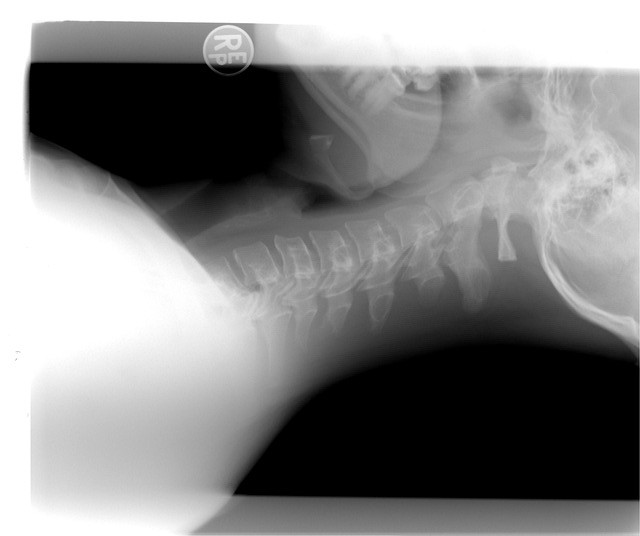

1. Plain radiographs (AP pelvis and Judet views) help identify fracture lines and alignment.

2. CT scanning with 3D reconstruction is almost always needed to define the fracture pattern and plan surgery.

3. Additional studies, such as vascular imaging or nerve conduction tests, may be used when complications are suspected.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to restore joint congruity, ensure stability, and promote early mobility while preventing long-term arthritis.

Non-operative Treatment

Non-operative care is reserved for stable, minimally displaced fractures or patients unable to tolerate surgery. Management includes traction, limited weight-bearing, and physiotherapy. Regular imaging is required to monitor alignment.

However, conservative management carries a higher risk of malunion and joint degeneration compared with surgical fixation.

Surgical Treatment

Most displaced acetabular fractures require open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). The key principles are anatomic reduction, stable fixation with plates and screws, and protection of soft tissues and nerves.

Surgical approaches depend on the fracture pattern:

– The Kocher-Langenbeck approach is used for posterior fractures.

– The ilioinguinal or modified Stoppa approaches are used for anterior or medial fractures.

– Combined or extensile approaches may be needed for both-column injuries.

In older patients with comminuted fractures or pre-existing arthritis, acute total hip replacement may be considered.

Postoperative Care and Rehabilitation

Hospitalization usually lasts about one week. Early motion exercises are started as tolerated, progressing to active strengthening and gait training. Weight-bearing is typically restricted for 8 to 12 weeks.

Rehabilitation focuses on restoring range of motion, muscle strength, and safe mobility. Ongoing follow-up is essential to detect complications such as arthritis or fixation failure.

Complications and Prognosis

Common complications include:

– Malreduction or loss of fixation

– Post-traumatic arthritis

– Heterotopic ossification

– Avascular necrosis of the femoral head

– Sciatic nerve palsy

– Deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism

– Infection or hardware irritation

Better outcomes are associated with younger age, good bone quality, early surgical treatment, and accurate reduction. Older age, female sex, posterior wall involvement, femoral head injury, and nerve damage predict poorer results and higher risk of requiring total hip replacement later.

Prevention and Patient Education

Seat belt use and road safety measures help reduce high-energy trauma. In older adults, fall prevention and osteoporosis management are key strategies to lower fracture risk.

Regular exercise, calcium and vitamin D intake, and home safety modifications can help prevent future injuries. Follow-up imaging and clinical review are important for long-term joint health.

References

Rommens, P. M., & Hessmann, M. H. (1999). Acetabular fractures. Der Unfallchirurg, 102(8), 591-610.

Moed, B. R., Paul, H. Y., & Gruson, K. I. (2003). Functional outcomes of acetabular fractures. JBJS, 85(10), 1879-1883.

Kelly, J., Ladurner, A., & Rickman, M. (2020). Surgical management of acetabular fractures–a contemporary literature review. Injury, 51(10), 2267-2277.