A wrist fracture refers to a break in one or more of the bones around the wrist joint, most commonly the distal end of the radius. Because the wrist plays a key role in hand movement, grip strength and daily activities, a fracture in this region may significantly affect function and requires prompt assessment and appropriate treatment.

Anatomy and Biomechanics

The wrist encompasses the distal ends of the forearm bones (radius and ulna) and the proximal row of carpal bones. The distal radius typically forms the main articulation with the carpus. Ligaments, tendons, and the joint capsule stabilise the wrist during load-bearing, flexion, extension, and rotation.

When a fracture occurs at the distal radius (or other wrist bones), the normal biomechanical load distribution is disrupted. The wrist may lose its normal alignment or joint surface integrity. As a result, restorative anatomy and restoration of alignment are important to maintain wrist range of motion, strength and avoid long-term joint degeneration.

Etiology and Risk Factors

Mechanism of Injury

The most common mechanism is a fall onto an outstretched hand, which drives force through the wrist and commonly fractures the distal radius. In younger individuals, high-energy trauma such as sports injuries, motor vehicle collisions or falls from height may produce complex wrist fracture patterns. In older adults, fractures often occur from lower-energy falls due to reduced bone strength.

Risk Factors

- Reduced bone density (osteopenia or osteoporosis)

- Advanced age, especially in post-menopausal women

- Participation in high-impact or contact sports

- Poor wrist proprioception, muscle weakness or prior injury

- Inadequate fall-protection or high-risk environments

Classification and Fracture Patterns

Wrist fractures encompass a broad spectrum of injuries that differ in location, fracture morphology, displacement, articular involvement, and the degree of comminution. The classification of these fractures assists clinicians in determining the appropriate treatment strategy, predicting potential complications, and estimating functional outcomes.

Wrist fractures vary widely in terms of location, displacement, joint involvement, and comminution. Examples include:

- Extra-articular fractures (do not involve the joint surface)

- Intra-articular fractures (extend into the wrist joint)

- Colles fracture (distal radius fracture with dorsal displacement)

- Smith fracture (distal radius fracture with volar displacement)

- Comminuted, unstable fractures with multiple fragments or associated ligament injury

Fracture classification is primarily based on anatomical location (distal radius, distal ulna, or carpal bones), the presence or absence of joint involvement, the direction of displacement, and the degree of soft tissue injury. The distal radius is the most frequently affected site, and several descriptive and formal classification systems are used to characterise these injuries.

Common Types of Wrist Fractures

1. Extra-articular fractures

These fractures occur proximal to the joint surface and do not extend into the radiocarpal joint. The joint alignment is typically preserved, but angulation or shortening of the distal fragment can alter wrist mechanics. These are often seen in lower-energy injuries and may be stable, allowing conservative management.

2. Intra-articular fractures

These fractures extend into the wrist joint, disrupting the articular surface. They are more likely to result in post-traumatic arthritis if anatomical reduction is not achieved. Intra-articular fractures often require precise imaging and, in many cases, surgical intervention to restore the joint surface and maintain long-term wrist function.

3. Colles fracture

This classic distal radius fracture occurs with dorsal displacement and angulation of the distal fragment, typically following a fall onto an outstretched hand. It is the most common pattern in older adults with osteoporotic bone. The deformity may result in a “dinner-fork” appearance of the wrist and frequently coexists with a fracture of the ulnar styloid process.

4. Smith fracture

Also known as a reverse Colles fracture, this injury involves volar (palmar) displacement of the distal radius fragment, usually following a fall onto a flexed wrist. Smith fractures tend to be more unstable than Colles fractures and often require surgical fixation to maintain reduction.

5. Barton fracture

This is an intra-articular fracture of the distal radius rim, which may involve either the dorsal or volar aspect. Because the fracture line extends into the joint and is often associated with dislocation or subluxation of the radiocarpal joint, it is inherently unstable and typically managed surgically.

6. Chauffeur’s fracture (radial styloid fracture)

A fracture of the radial styloid process is often caused by a direct blow or compression from the scaphoid against the radius. This injury may accompany carpal instability and can sometimes involve intra-articular extension, necessitating surgical repair for anatomical restoration.

7. Comminuted fractures

These fractures involve multiple fragments and significant disruption of bone architecture. They are often the result of high-energy trauma and are typically unstable. Management often requires surgical fixation using plates, screws, or external fixation devices to restore bone alignment and joint congruity.

8. Associated injuries

Wrist fractures may coexist with soft tissue injuries such as triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) tears, distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) disruption, and ligamentous injuries involving the scapholunate or lunotriquetral ligaments. These associated injuries may not be visible on initial imaging but can significantly affect long-term wrist function if not identified and treated appropriately.

Classification Systems

Several formal systems are used to categorise distal radius fractures for research and clinical decision-making. The Frykman classification considers articular involvement of the radiocarpal and distal radioulnar joints, while the AO/OTA classification system is more comprehensive, detailing fracture morphology, comminution, and joint surface disruption. The AO system classifies fractures into three main types:

Type A: Extra-articular fractures

Type B: Partial articular fractures

Type C: Complete articular fractures with metaphyseal comminution

Why classification matters

Fracture classification systems for the distal radius (wrist) are tools to (1) describe anatomy consistently, (2) guide treatment choices and prognosis, and (3) enable comparable data in research and audit. No single system is perfect: simpler schemes are easier to use but carry less anatomic detail, while more detailed systems (e.g., AO/OTA) describe morphology precisely but are more complex and less reproducible between observers.

Frykman classification – the essentials

The Frykman system (1967) is an early, radiograph-based scheme that classifies distal-radius fractures primarily by articular involvement (radiocarpal and/or distal radioulnar joint) and by whether an ulnar styloid fracture is present. It produces eight types:

1. Type I — Extra-articular radius fracture (no ulnar styloid).

2. Type II — Type I + ulnar styloid fracture.

3. Type III — Intra-articular involving the radiocarpal (radiocarpal joint) (no ulnar styloid).

4. Type IV — Type III + ulnar styloid fracture.

5. Type V — Intra-articular involving the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) (no ulnar styloid).

6. Type VI — Type V + ulnar styloid fracture.

7. Type VII — Intra-articular involving both radiocarpal and DRUJ (no ulnar styloid).

8. Type VIII — Type VII + ulnar styloid fracture.

Strengths and limitations

Strength: simple and quick to apply on standard AP radiographs; highlights whether the joint surfaces and the ulnar styloid are involved, features historically thought to influence instability and DRUJ injury.

Limitation: it does not describe fracture displacement, comminution, metaphyseal pattern, or fracture level; reliability (inter-observer agreement) is modest to poor in modern studies, and it is of limited value when CT is available or when precise morphology matters for surgical planning. For these reasons, many clinicians use Frykman only as a quick descriptor, not as a surgical decision algorithm.

AO/OTA classification – comprehensive, hierarchical

The AO/OTA system (widely taught and used in trauma literature) is hierarchical and more granular. For distal radius fractures, it uses a three-level scheme:

- First level (letters A–C) – joint involvement:

- A (extra-articular) – articular surface not involved.

- B (partial articular) – part of the articular surface remains attached to the shaft (partial intra-articular).

- C (complete articular) – articular surface is separated from the shaft and there is metaphyseal comminution (complete intra-articular).

- Second and third levels (numbers) – further subdivide based on fracture pattern, location, and comminution. For example, under the distal radius (coded as 2R3 in AO/OTA notation):

- 2R3A1 – radial styloid avulsion (simple extra-articular subtype).

- 2R3A2 – simple extra-articular with volar or dorsal displacement.

- 2R3A3 – wedge or multifragmentary extra-articular.

- Types B and C have analogous subgroups that describe the degree of articular involvement and comminution (and can indicate volar/dorsal, marginal impaction, etc.). The full compendium contains 20+ specific subcodes for distal radius patterns.

Clinical utility of AO/OTA

Strengths: very detailed, links anatomy to potential instability (comminution, joint disruption), and supports standardized reporting in trials and registries. It can capture injury complexity that affects fixation strategy (plate vs. external fixator, fragment-specific fixation), the likelihood of articular step-off, and prognosis.

Limitations: complexity reduces day-to-day inter-observer reliability unless users are trained; it is more time-consuming to code and still sometimes lacks specific descriptors that CT or fragment-specific systems (e.g., Melone) capture. Clinicians often supplement AO coding with descriptive notes (displacement, volar tilt, radial shortening, intra-articular step) that influence management.

Practical comparison (Frykman vs AO/OTA)

- Scope: Frykman = articular involvement + ulnar styloid (simple). AO/OTA = articular involvement plus fracture level, comminution, displacement, and subtypes (detailed).

- Use case: Frykman is quick for broad epidemiology or historical reports. AO/OTA is preferred for surgical planning, research that requires precise morphology, quality registries, and when communicating about fixation strategy.

- Reliability: Neither is perfectly reproducible; AO/OTA generally has better content validity for surgical decision-making but still requires training for consistent use. Several studies have shown only moderate inter-observer agreement across multiple systems.

How classification affects management and research

- Extra-articular (Frykman I/II or AO A) fractures may be treated nonoperatively if alignment is acceptable and the fracture is stable; comminuted extra-articular patterns (AO A3) are more prone to collapse and may need fixation.

- Partial and complete intra-articular fractures (Frykman III–VIII; AO B and especially C) carry higher risk of post-traumatic arthritis, require more attention to articular congruity, and often need open reduction and internal fixation to restore joint surface and length.

- For research, using AO/OTA (or adding CT-based subclassification) improves ability to stratify patients by injury severity and compare interventions; simpler schemes may be acceptable for large epidemiologic descriptions but reduce granularity.

Practical tips for clinicians

- Record both a classification code (AO/OTA, where possible) and a brief descriptive sentence (e.g., 2R3C2 – complete articular with dorsal comminution, 3 mm intra-articular step at scaphoid fossa, ulnar styloid fragment present) – this balances standardization and actionable detail.

- Use plain radiographs for initial classification; consider CT for complex intra-articular fractures to define fragment geometry and plan fragment-specific fixation. Newer CT-based schemes and fragment-based classifications are emerging for these settings.

- Frykman = simple, eight-type, focused on radiocarpal/DRUJ involvement and ulnar styloid; limited for surgical planning.

- AO/OTA = hierarchical, three main groups (A extra-articular, B partial articular, C complete articular) with many subtypes that describe comminution and specific fracture patterns; better for operative decision-making and research, but more complex.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms

Patients with a wrist fracture typically present with:

- Sudden onset wrist pain following trauma

- Swelling, bruising, or tenderness around the wrist

- Possible deformity or visible angulation at the wrist

- Inability or difficulty moving the wrist or hand, or gripping objects

- Numbness or tingling in the fingers if nerves are affected

Physical Examination

A thorough physical examination is essential in the assessment of a wrist fracture to evaluate the extent of the injury, identify potential complications, and detect any associated soft tissue or neurovascular damage. The examination should be conducted systematically and compared with the contralateral (uninjured) wrist whenever possible to identify subtle deformities or asymmetries.

General Observation

The wrist should be inspected for swelling, bruising, deformity, or abnormal positioning of the hand. In many cases, a visible deformity may indicate displacement of the distal fracture fragment. A “dinner-fork” appearance suggests a Colles fracture (dorsal displacement), while a “garden-spade” deformity is more consistent with a Smith fracture (volar displacement). Swelling is typically most pronounced around the distal radius and dorsum of the wrist. Ecchymosis may extend into the forearm or hand within several hours of injury.

The examiner should note any open wounds, lacerations, or puncture sites that could indicate an open fracture or concomitant soft-tissue trauma. Open injuries require immediate attention to reduce the risk of infection.

Palpation

Gentle palpation is performed to localize tenderness and assess the extent of bone and soft-tissue injury. Point tenderness over the distal radius is highly suggestive of a fracture. The examiner should also palpate the distal ulna, carpal bones (particularly the scaphoid and lunate), and the base of the thumb to exclude associated fractures or ligamentous injuries.

Crepitus or abnormal mobility at the distal radius may be present in displaced fractures, although excessive manipulation should be avoided to prevent further tissue damage or neurovascular compromise. The integrity of the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) should be checked by palpating for instability or pain with pronation and supination movements.

Range of Motion and Function

Wrist motion is often limited due to pain, swelling, or mechanical obstruction. The patient’s ability to flex, extend, and rotate the wrist should be assessed carefully, but only within a pain-free range. Grip strength is usually diminished, reflecting both pain inhibition and loss of mechanical leverage from the fracture. Patients may also have difficulty with forearm rotation, particularly if the DRUJ or interosseous membrane is involved.

Neurovascular Assessment

Neurovascular integrity must be evaluated in all wrist injuries, as swelling or fracture displacement may compress nearby structures. The median nerve, which passes through the carpal tunnel, is at particular risk in distal radius fractures. Sensation should be tested in the palmar aspect of the thumb, index, middle, and radial half of the ring finger. Weakness of thumb opposition or numbness in these digits may indicate acute median nerve compression.

The ulnar nerve (sensation over the little finger and ulnar side of the ring finger) and radial nerve (sensation over the dorsal thumb and web space) should also be assessed. Capillary refill, skin temperature, and pulse palpation (radial and ulnar arteries) help confirm adequate blood flow to the hand. Delayed capillary refill or pallor may signal vascular compromise, requiring urgent intervention.

Evaluation of Associated Injuries

Because wrist fractures often occur with additional soft-tissue or ligamentous damage, a focused examination should include assessment for:

- Distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) instability: Assessed by gently rotating the forearm through pronation and supination while stabilising the distal radius; excessive motion or crepitus suggests DRUJ disruption.

- Carpal instability: Pain or tenderness at the scapholunate interval or lunotriquetral area may indicate ligament injury. The Watson test may be cautiously performed if tolerated to assess scapholunate stability.

- Scaphoid fracture: Tenderness in the anatomic snuffbox, pain on axial compression of the thumb, or pain with wrist extension may indicate an associated scaphoid injury.

- Tendon involvement: Rupture of the extensor pollicis longus (EPL) tendon may occur in certain distal radius fractures, often presenting later during the recovery phase.

Functional and Comparative Testing

If pain allows, the examiner may assess the alignment of the radial and ulnar styloid processes, the relationship of the radial and ulnar heads, and the overall contour of the wrist. Functional tasks such as finger flexion and extension or thumb opposition may be gently tested to evaluate the impact on dexterity. Comparison with the uninjured wrist helps to determine subtle differences in alignment, swelling, or motion range.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Imaging

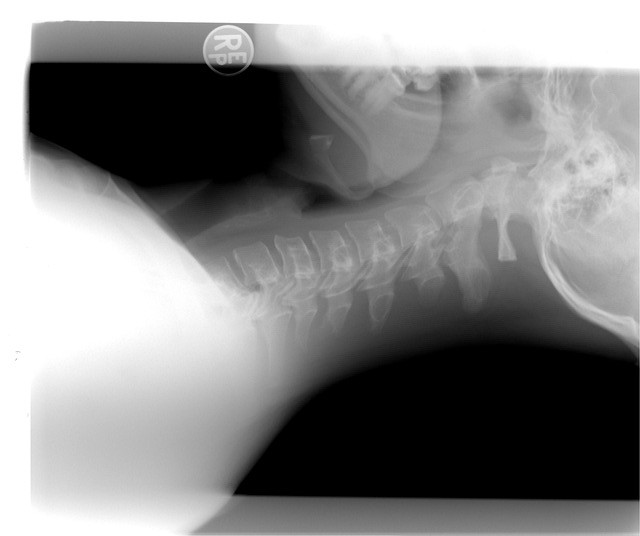

The initial diagnostic assessment of a suspected distal radius fracture begins with plain radiographs of the wrist, including anteroposterior (AP) and true lateral views. These images are used to evaluate fracture lines, displacement, angulation, comminution, and articular involvement. Radiographs also allow for preliminary classification of the fracture pattern.

The Frykman classification can be applied to plain films to identify whether the fracture involves the radiocarpal and/or distal radioulnar joints, and whether an ulnar styloid fracture is present.

The AO/OTA classification system provides a more comprehensive morphological description, categorizing fractures into:

- Type A: Extra-articular fractures (no joint surface involvement)

- Type B: Partial articular fractures (a portion of the joint remains attached to the shaft)

- Type C: Complete articular fractures with metaphyseal comminution and separation of the articular surface from the shaft.

This systematic classification assists in determining fracture complexity, instability, and the need for operative intervention.

In cases where the fracture pattern is complex or intra-articular, computed tomography (CT) is recommended to delineate fragment configuration, articular step-off, and metaphyseal comminution. CT-based reconstructions are particularly useful for accurate AO subclassification and surgical planning. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be reserved for suspected soft-tissue injuries, such as ligament tears or occult fractures not visible on radiographs.

Additional Assessment

Beyond fracture morphology, clinicians should evaluate for associated injuries, including ligamentous disruptions, carpal instability, and distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) involvement, as these may influence both classification and treatment strategy. Assessment of bone quality is essential, especially in elderly patients or those with suspected osteoporosis, as poor bone stock can affect fixation stability and prognosis.

Careful attention to radiographic alignment parameters, such as radial height, inclination, volar tilt, and ulnar variance, supports accurate classification, guides treatment planning, and helps predict functional outcomes.

Treatment

The overarching goal of treatment for distal radius fractures is to restore anatomic alignment, achieve stable fixation when necessary, promote fracture healing, restore wrist function, and minimise long-term complications such as stiffness, malunion, or post-traumatic arthritis.

The treatment strategy is primarily determined by the fracture classification, stability, patient factors such as age, bone quality, and activity level, as well as functional demands. Classification systems such as Frykman and AO/OTA provide a structured framework to guide these decisions.

Frykman Type I and II (extra-articular) and AO Type A fractures are often stable and amenable to conservative management.

Frykman Type III to VIII (intra-articular) and AO Type B or C fractures frequently demonstrate instability, displacement, or articular incongruity, often necessitating surgical intervention to restore joint congruity and prevent degenerative changes.

Nonoperative (Conservative) Treatment

Nonoperative management is appropriate for stable, minimally displaced extra-articular fractures or in patients with low functional demands. The main objectives are to maintain reduction, allow biological healing, and preserve motion.

Key components include:

- Immobilisation using a below-elbow cast or volar splint for approximately 4 to 6 weeks, depending on fracture stability and radiographic evidence of healing.

- Elevation and cryotherapy to manage early swelling and pain.

- Analgesic and anti-inflammatory therapy as indicated.

- Radiographic monitoring, typically at one to two weeks post-reduction, to ensure maintained alignment, particularly in potentially unstable AO Type A3 fractures.

- Gradual rehabilitation after immobilisation, beginning with active range of motion exercises, followed by progressive strengthening to restore function and grip strength.

Close follow-up is essential, as secondary displacement during healing may compromise functional outcome and alignment parameters such as radial height, volar tilt, and ulnar variance.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical management is indicated for fractures that are displaced, unstable, comminuted, or intra-articular, as well as for patients requiring early return to function.

Common indications include:

- AO Type B (partial articular) and Type C (complete articular) fractures with incongruent joint surfaces.

- Metaphyseal comminution or loss of radial length after closed reduction.

- Dorsal tilt greater than 10 degrees, radial shortening greater than 3 mm, or articular step-off greater than 2 mm on post-reduction imaging.

Surgical options include:

- Open reduction and internal fixation with volar locking plates and screws is the most common approach.

- External fixation, often combined with percutaneous pinning, for highly comminuted or osteoporotic fractures.

- Percutaneous pinning for select extra-articular patterns in younger patients with good bone quality.

Following surgery, early wrist mobilisation is encouraged once fixation stability permits, typically within the first one to two weeks, to prevent stiffness and promote tendon gliding. A structured physiotherapy program focusing on range of motion, proprioception, and progressive strengthening supports functional recovery.

Regular postoperative imaging is recommended to verify maintenance of reduction, hardware position, and fracture union.

Rehabilitation and Follow-Up

Early rehabilitation is critical. After immobilisation or surgery, therapy focuses on restoring range of motion, reducing stiffness, regaining strength of wrist and hand, and gradually returning to full function including grip and dexterity tasks. Follow-up includes assessment of healing, alignment, joint function, and checking for late complications such as post-traumatic arthritis, reduced motion or chronic pain. Return to work or sports is guided by treatment success, fracture stability, and rehabilitation progress.

Complications and Prognosis

Potential complications include:

- Malalignment or loss of reduction leading to poor wrist mechanics or arthritis

- Joint stiffness, decreased range of motion or strength

- Nonunion or delayed healing (more common in high-energy injuries or poor bone quality)

- Osteoarthritis of the wrist or radiocarpal joint especially after intra-articular fractures

- Nerve or blood vessel injury at the time of fracture or surgical repair

- Complex regional pain syndrome or chronic pain

Overall prognosis is good for many wrist fractures, especially when treated promptly and appropriately. Younger patients with good bone quality often recover full function. Older patients, those with complex fractures or poor bone quality may have residual limitations or prolonged recovery.

Prevention and Patient Education

Key preventive strategies include:

- Strengthening wrist, forearm and hand muscles and improving wrist proprioception

- Fall prevention programmes especially in older adults (home safety, balance training)

- Addressing bone health including screening for osteoporosis, ensuring adequate calcium and vitamin D intake

- Use of protective wrist gear during sports or high-risk activities

- In the event of a fall onto an outstretched hand, prompt evaluation is recommended even if pain seems mild

References

Hanel, D. P., Jones, M. D., & Trumble, T. E. (2002). Wrist fractures. Orthopedic Clinics, 33(1), 35-57.

Sharma, M., Choudhury, S. R., Sinha, A., & Prakash, M. (2025). Multimodality Imaging in Wrist Fractures and Dislocations. Indian Journal of Radiology and Imaging.

Lim, B., Talbot, S., Jassim, S., Quinn, E. P., & Shaalan, M. (2025). Kirschner’s Wire versus Casts in Wrist Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Wrist Surgery.