Marfan syndrome is a rare, inherited disorder of the connective tissue that affects the body’s skeletal, cardiovascular, ocular, and integumentary systems. First described in 1896 by French pediatrician Antoine Marfan, the condition arises due to abnormalities in the body’s connective tissues, which provide strength, support, and elasticity to various structures in the body (1). The syndrome varies widely in severity, even among members of the same family, making early detection and careful management essential. Though there is no cure, with proper treatment and monitoring, individuals with Marfan syndrome can lead long, fulfilling lives.

Symptoms

The symptoms of Marfan syndrome can vary significantly from person to person, depending on the systems affected. Some individuals exhibit only mild signs, while others may experience life-threatening complications (1). Common symptoms include:

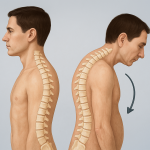

- Skeletal abnormalities: People with Marfan syndrome are often tall and thin with disproportionately long arms, legs, fingers, and toes (arachnodactyly). They may also have scoliosis (curved spine), a sunken chest (pectus excavatum), or a protruding chest (pectus carinatum).

- Eye problems: Lens dislocation (ectopia lentis) is a hallmark feature, occurring in more than half of individuals with the syndrome. Nearsightedness, early-onset glaucoma, and cataracts are also common.

- Cardiovascular complications: The most serious risks involve the heart and blood vessels. The aorta, the major artery carrying blood from the heart, may become enlarged or weakened (aortic dilation or aneurysm), increasing the risk of dissection or rupture a potentially fatal condition. Mitral valve prolapse is also frequently observed (2).

- Other features: Individuals may have stretch marks unrelated to weight changes, flat feet, or a high-arched palate. Lung complications like spontaneous pneumothorax (collapsed lung) may occur in some cases.

Causes

Marfan syndrome is caused by a mutation in the FBN1 gene, which encodes fibrillin-1, a protein crucial for the formation of elastic fibers in connective tissue. The defective fibrillin-1 protein leads to abnormalities in the structure and function of connective tissues throughout the body. This mutation also results in increased activity of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), a protein that affects cell growth and development and contributes to many of the features of Marfan syndrome (2).

The condition follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, meaning that a child only needs to inherit the mutated gene from one parent to be affected. In about 75% of cases, the mutation is inherited from an affected parent. However, up to 25% of cases result from a new (de novo) mutation with no family history.

Risk Factors

The primary risk factor for Marfan syndrome is family history. If one parent has the disorder, there is a 50% chance their child will inherit the condition. There is no known influence of sex, race, or ethnicity on the prevalence of Marfan syndrome, although it affects males and females equally. Environmental or lifestyle factors do not contribute to the risk of developing the syndrome, as it is strictly genetic in origin (3).

Diagnosis

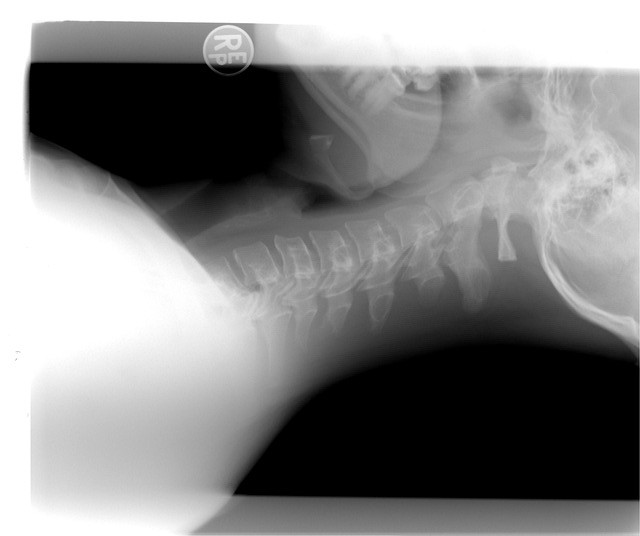

Diagnosing Marfan syndrome can be challenging due to the variability in symptoms and the overlap with other connective tissue disorders. A diagnosis is often based on a combination of (2):

- Clinical evaluation: A detailed physical examination focusing on skeletal, ocular, and cardiovascular signs.

- Family history: Documentation of Marfan features in close relatives.

- Imaging studies: Echocardiography or MRI to evaluate the aorta and heart valves.

- Ophthalmologic examination: To detect lens dislocation and other eye issues.

- Genetic testing: Identification of an FBN1 gene mutation can confirm the diagnosis, especially in ambiguous cases.

A set of diagnostic criteria known as the Ghent Nosology is used to establish a definitive diagnosis, integrating genetic findings and clinical features.

Treatment Options

There is currently no cure for Marfan syndrome, but treatment focuses on managing symptoms and preventing complications, particularly cardiovascular issues. A multidisciplinary approach involving cardiologists, orthopedic specialists, ophthalmologists, and genetic counselors is typically recommended.

Key treatment strategies include

- Medications: Beta-blockers or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), such as losartan, are often prescribed to reduce stress on the aorta by lowering blood pressure and slowing the heart rate (3).

- Surgery: In cases of significant aortic enlargement or mitral valve prolapse, surgical repair or replacement may be necessary to prevent life-threatening complications.

- Vision correction: Glasses or contact lenses can address common vision problems, while surgery may be required for lens dislocation or cataracts.

- Orthopedic care: Bracing or surgery may be needed to correct spinal curvature or chest deformities.

- Lifestyle modifications: Individuals are typically advised to avoid strenuous physical activity or contact sports that could stress the heart or joints. Regular, low-impact exercise like swimming or walking is encouraged.

Living With or Prevention

While Marfan syndrome cannot be prevented, early diagnosis and lifelong monitoring are key to managing the condition effectively and minimizing health risks. With ongoing care, most people with Marfan syndrome live well into adulthood and can have a normal lifespan (4).

Living with Marfan syndrome involves

- Regular check-ups: Annual cardiovascular evaluations to monitor aortic size and function.

- Genetic counseling: For affected individuals and families considering having children.

- Patient education: Understanding the signs of aortic dissection (e.g., sudden chest or back pain) is critical for timely emergency care.

- Psychosocial support: Connecting with support groups or counseling can help individuals and families cope with the emotional aspects of living with a chronic genetic disorder.

References

- Milewicz DM, Braverman AC, De Backer J, Morris SA, Boileau C, Maumenee IH, Jondeau G, Evangelista A, Pyeritz RE. Marfan syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021 Sep 2;7(1):64. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00298-7. Erratum in: Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022 Jan 17;8(1):3. doi: 10.1038/s41572-022-00338-w. PMID: 34475413; PMCID: PMC9261969.

- Stengl R, Ágg B, Pólos M, Mátyás G, Szabó G, Merkely B, Radovits T, Szabolcs Z, Benke K. Potential predictors of severe cardiovascular involvement in Marfan syndrome: the emphasized role of genotype-phenotype correlations in improving risk stratification-a literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021 May 31;16(1):245. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01882-6. PMID: 34059089; PMCID: PMC8165977.

- Deleeuw V, De Clercq A, De Backer J, Sips P. An Overview of Investigational and Experimental Drug Treatment Strategies for Marfan Syndrome. J Exp Pharmacol. 2021 Aug 11;13:755-779. doi: 10.2147/JEP.S265271. PMID: 34408505; PMCID: PMC8366784.

- Trawicka A, Lewandowska-Walter A, Majkowicz M, Sabiniewicz R, Woźniak-Mielczarek L. Health-Related Quality of Life of Patients with Marfan Syndrome-Polish Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jun 2;19(11):6827. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19116827. PMID: 35682408; PMCID: PMC9180829.