Lumbago is a general term that refers to pain in the lower back region, affecting millions of people worldwide. It is not a diagnosis in itself but rather a symptom of various underlying medical conditions or musculoskeletal problems (1). The term “lumbago” has been used historically to describe pain located in the lumbar spine, the area between the bottom of the ribcage and the top of the legs. This pain can range from a dull ache to a sharp, stabbing sensation and can be acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term). While lumbago is rarely caused by serious diseases, it can significantly affect daily activities, work, and quality of life.

Symptoms

The primary symptom of lumbago is pain in the lower back, but the intensity and characteristics can vary widely. Common symptoms include

- Dull, aching pain: Often localized in the lumbar region.

- Sharp or stabbing pain: May radiate to the buttocks, thighs, or even legs if nerves are involved.

- Stiffness and reduced mobility: Difficulty bending, twisting, or standing up straight.

- Muscle spasms: Sudden, involuntary contractions of the back muscles.

- Pain worsening with movement: Activities such as lifting, sitting for long periods, or changing positions can aggravate the discomfort.

- Improvement with rest: In some cases, lying down or reclining may provide relief.

Symptoms may come on suddenly (as in acute lumbago) or develop gradually over time in chronic cases (1).

Causes

Lumbago can stem from various causes, ranging from benign mechanical issues to more serious health conditions (2). Common causes include

- Muscle or ligament strain: Overuse, poor posture, heavy lifting, or sudden awkward movements can strain the back muscles and ligaments.

- Degenerative disc disease: Wear and tear of the spinal discs over time can lead to pain and inflammation.

- Herniated or bulging discs: When spinal discs protrude or rupture, they may press on nearby nerves, causing pain.

- Arthritis: Osteoarthritis and other forms of arthritis can affect the spine and lead to lower back pain.

- Spinal stenosis: Narrowing of the spinal canal that puts pressure on the spinal cord and nerves.

- Spondylolisthesis: A condition in which a vertebra slips out of place onto the bone below it.

- Poor posture or sedentary lifestyle: Extended sitting or improper ergonomics can contribute to chronic lower back discomfort.

Less common but more serious causes include infections (e.g., spinal osteomyelitis), tumors, or fractures due to osteoporosis.

Risk Factors

Several factors can increase the risk of developing lumbago, including

- Age: People between 30 and 50 are more likely to experience back pain due to natural spinal degeneration.

- Occupational hazards: Jobs that require heavy lifting, repetitive movements, or prolonged sitting can strain the back.

- Obesity: Excess body weight puts additional stress on the spine and surrounding muscles.

- Sedentary lifestyle: Lack of physical activity weakens the muscles that support the spine.

- Smoking: Reduces blood flow to spinal tissues and accelerates disc degeneration.

- Poor posture: Slouching or improper body mechanics can strain the lumbar region.

- Previous back injuries: A history of back problems may increase susceptibility to lumbago.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing lumbago begins with a detailed medical history and physical examination. A healthcare provider may assess range of motion, reflexes, muscle strength, and sensation to identify nerve involvement or musculoskeletal issues (2).

Additional diagnostic tools may include

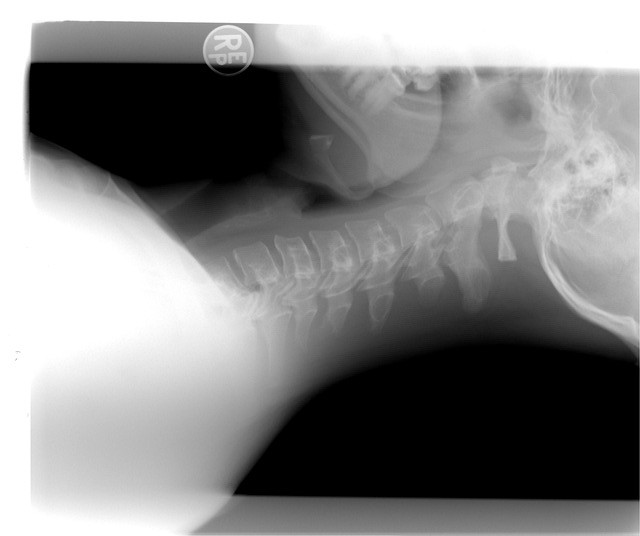

- X-rays: To check for bone abnormalities such as fractures, arthritis, or vertebral alignment.

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): Offers detailed images of soft tissues, including discs, muscles, and nerves.

- CT scans: Useful in identifying spinal stenosis, tumors, or other structural issues.

- Blood tests: If infection or systemic disease is suspected.

- Electromyography (EMG): Helps assess nerve and muscle function when nerve compression is suspected.

The diagnosis helps determine whether the pain is mechanical (due to structural issues) or related to more serious underlying conditions.

Treatment Options

Treatment for lumbago depends on the severity, duration, and underlying cause of the pain. Options range from conservative home care to advanced medical interventions (2).

Self-Care and Lifestyle Modifications

- Rest (short-term): Brief periods of rest may help, but extended inactivity can worsen symptoms.

- Heat or cold therapy: Applying a heating pad or ice pack to the affected area can reduce pain and inflammation.

- Exercise: Gentle stretching and strengthening exercises help restore mobility and support the spine.

- Ergonomic adjustments: Improving posture and workstation setup can prevent recurrent pain.

Medications

- Pain relievers: Over-the-counter medications like ibuprofen or acetaminophen can reduce discomfort.

- Muscle relaxants: For muscle spasms associated with acute lumbago.

- Topical analgesics: Creams or patches that provide localized pain relief.

Physical Therapy

- A trained therapist can design a personalized exercise and stretching regimen to improve flexibility, strength, and posture.

- Techniques such as spinal adjustments, massage therapy, or manipulations may offer relief for certain individuals.

Injections

- Corticosteroid injections near the spine can reduce inflammation in cases of severe pain due to nerve involvement.

Surgery

-

- Rarely required, but may be necessary for conditions like herniated discs, spinal stenosis, or structural deformities not responding to conservative care.

Living With or Prevention

Living with lumbago can be challenging, but many people recover fully with proper management (3). Preventive strategies and lifestyle changes can also reduce the risk of recurrence

- Regular exercise: Strengthens core muscles that support the back.

- Weight management: Reduces stress on the spine.

- Proper lifting techniques: Use your legs instead of your back to lift heavy objects.

- Ergonomic workplace setup: Ensure your chair, desk, and monitor promote good posture.

- Quit smoking: To improve spinal disc health.

- Stretch frequently: Especially if you sit for long periods during work (3).

References

- Farley T, Stokke J, Goyal K, DeMicco R. Chronic Low Back Pain: History, Symptoms, Pain Mechanisms, and Treatment. Life (Basel). 2024 Jun 27;14(7):812. doi: 10.3390/life14070812. PMID: 39063567; PMCID: PMC11278085.

- IJzelenberg W, Oosterhuis T, Hayden JA, Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Rubinstein SM, de Zoete A. Exercise therapy for treatment of acute non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Aug 30;8(8):CD009365. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009365.pub2. PMID: 37646368; PMCID: PMC10467021.

- Liu Q, Liu X, Lin H, Sun Y, Geng L, Lyu Y, Wang M. Occupational low back pain prevention capacity of nurses in China: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar 16;11:1103325. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1103325. PMID: 37006565; PMCID: PMC10060810.