Osteomalacia is a medical condition characterized by the softening of bones due to impaired bone mineralization. This disorder primarily affects adults and is often considered the adult counterpart of rickets, which occurs in children. The softening of bones in osteomalacia leads to bone pain, muscle weakness, and a higher risk of fractures (1). Unlike osteoporosis, which involves reduced bone mass, osteomalacia results from defective bone formation or remodeling. Most commonly caused by a deficiency in vitamin D, osteomalacia is both preventable and treatable if diagnosed early. Understanding its symptoms, underlying causes, and treatment approaches is essential for effective management and prevention (1).

Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of osteomalacia may be subtle in the early stages but typically worsen over time as the bone demineralization progresses. Common symptoms include (1):

- Bone pain, particularly in the hips, lower back, legs, and ribs.

- Muscle weakness, especially in the proximal muscles such as those in the thighs and shoulders.

- Difficulty walking or waddling gait due to weakened muscles and bones.

- Fractures or pseudofractures (Looser’s zones), often with minimal trauma.

- Fatigue and general discomfort, possibly accompanied by a sense of heaviness in the limbs.

- Spasms or cramps, sometimes resulting from low calcium levels.

In some cases, individuals may experience numbness around the mouth or in the extremities, along with symptoms of hypocalcemia like tingling sensations or tetany.

Causes

The primary cause of osteomalacia is a deficiency in vitamin D, which is essential for calcium and phosphate absorption in the body. Several factors can contribute to this deficiency or hinder the process of bone mineralization, including (2).

- Inadequate sunlight exposure: Sunlight helps the skin synthesize vitamin D; lack of exposure, especially in elderly or housebound individuals, increases the risk.

- Poor dietary intake: A diet lacking in vitamin D, calcium, or phosphate contributes significantly to osteomalacia.

- Malabsorption syndromes: Conditions like celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, or gastric bypass surgery can impair the absorption of essential nutrients.

- Liver and kidney disorders: These organs are crucial for converting vitamin D into its active form. Impairment in function can lead to deficiencies.

- Certain medications: Drugs such as anticonvulsants (e.g., phenytoin), antiretrovirals, and some chemotherapy agents may interfere with vitamin D metabolism.

- Genetic disorders: Rare inherited conditions can disrupt phosphate metabolism, leading to osteomalacia.

Risk Factors

Several factors increase an individual’s susceptibility to osteomalacia

- Age: Elderly individuals are at a higher risk due to decreased dietary intake and limited sun exposure.

- Geographical location: People living in regions with limited sunlight, particularly during the winter months, are more prone to vitamin D deficiency.

- Dark skin pigmentation: Higher melanin levels can reduce the skin’s ability to produce vitamin D from sunlight.

- Obesity: Excess body fat can impair vitamin D metabolism and storage.

- Chronic illnesses: Conditions affecting the liver, kidneys, or gastrointestinal system raise the risk.

- Vegetarian or vegan diet: Individuals avoiding animal products may lack sufficient vitamin D and calcium unless properly supplemented (2).

Diagnosis

Diagnosing osteomalacia involves a combination of clinical assessment, laboratory tests, and imaging studies. A healthcare provider may suspect osteomalacia based on symptoms and physical examination, particularly muscle weakness and bone tenderness (3). Common diagnostic methods include

- Blood tests: These may show low levels of vitamin D, calcium, and phosphate, along with elevated alkaline phosphatase.

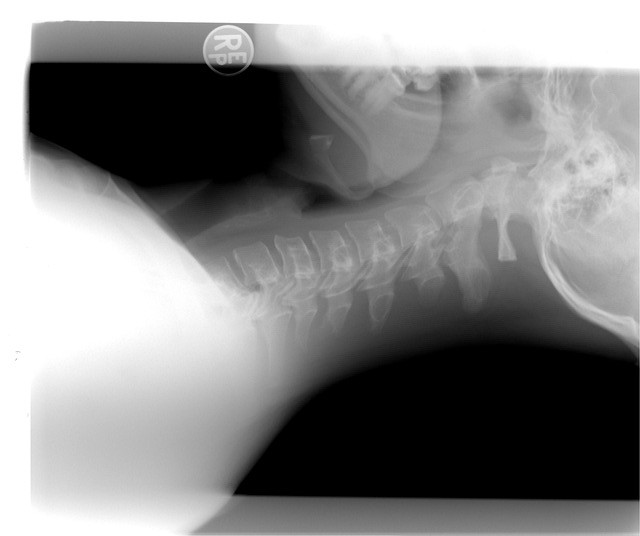

- X-rays: Imaging may reveal characteristic changes like Looser’s zones—narrow bands of radiolucency often seen in the ribs, pelvis, and long bones.

- Bone density scan (DEXA): Though not specific, it may indicate decreased bone mineral density.

- Bone biopsy: In rare cases, a biopsy can confirm the diagnosis by showing inadequate mineralization.

Timely and accurate diagnosis is crucial for preventing complications such as persistent pain, deformities, and fractures.

Treatment Options

The treatment of osteomalacia focuses on correcting the underlying cause and replenishing deficient nutrients (3). Key components include

- Vitamin D supplementation: Oral or intramuscular vitamin D (cholecalciferol or ergocalciferol) is the cornerstone of treatment. Dosage depends on the severity of deficiency and individual response.

- Calcium and phosphate supplements: These are often provided in conjunction with vitamin D, especially in cases involving dietary deficiency or malabsorption.

- Sunlight exposure: Encouraging safe exposure to sunlight helps boost natural vitamin D production.

- Treating underlying conditions: Addressing any gastrointestinal, renal, or hepatic disorders that contribute to malabsorption or impaired metabolism is essential.

- Monitoring and follow-up: Regular follow-up ensures normalization of vitamin D, calcium, and phosphate levels, as well as resolution of symptoms.

In cases involving genetic or complex metabolic causes, treatment may require specialized medications such as calcitriol or phosphate-binding agents.

Living With or Prevention

Living with osteomalacia can be challenging, especially if the diagnosis is delayed. However, with appropriate treatment, most people experience significant improvement in symptoms and quality of life. Patients are advised to

- Adhere to prescribed supplements and follow-up regimens (4).

- Engage in physical activity suited to their strength and mobility to maintain bone health and prevent further weakening.

- Adapt home environments to reduce fall risk, particularly for those with impaired balance or muscle weakness.

Preventing osteomalacia is often achievable through

- Adequate vitamin D intake: This includes both dietary sources (such as fatty fish, fortified dairy products, and egg yolks) and supplements if necessary.

- Regular sun exposure: About 10–30 minutes of sun exposure several times per week, depending on skin tone and geography, is generally sufficient.

- Routine health check-ups: Monitoring nutrient levels in at-risk populations (e.g., elderly, those with chronic illnesses) helps catch deficiencies early.

References

- Cianferotti L. Osteomalacia Is Not a Single Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Nov 28;23(23):14896. doi: 10.3390/ijms232314896. PMID: 36499221; PMCID: PMC9740398.

- Takedani K, Notsu M, Koike S, Yamauchi M, Mori T, Sohara E, Yamauchi A, Yoshikane K, Ito T, Kanasaki K. Osteomalacia caused by atypical renal tubular acidosis with vitamin D deficiency: a case report. CEN Case Rep. 2021 May;10(2):294-300. doi: 10.1007/s13730-020-00561-y. Epub 2021 Jan 4. PMID: 33398781; PMCID: PMC8019446.

- Liu S, Zhou X, Liu Y, Zhang J, Xia W. Preoperative evaluation and orthopedic surgical strategies for tumor-induced osteomalacia. J Bone Oncol. 2024 Mar 28;45:100600. doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2024.100600. PMID: 38577550; PMCID: PMC10990903.

- Minisola S, Barlassina A, Vincent SA, Wood S, Williams A. A literature review to understand the burden of disease in people living with tumour-induced osteomalacia. Osteoporos Int. 2022 Sep;33(9):1845-1857. doi: 10.1007/s00198-022-06432-9. Epub 2022 May 28. PMID: 35643939; PMCID: PMC9463218.