Antley‑Bixler Syndrome (ABS) is a rare and complex congenital disorder characterized by skeletal abnormalities, craniofacial malformations, and, in some cases, hormonal disruptions. First described in 1975 by Antley and Bixler, the condition is extremely uncommon, with fewer than 100 reported cases in the medical literature. ABS falls under the category of craniosynostosis syndromes—a group of disorders in which the bones in a baby’s skull join together too early, affecting skull and facial growth.

ABS is genetically heterogeneous, meaning it can result from mutations in different genes. The condition affects both males and females and typically manifests at birth or during prenatal development. Although the severity and presentation vary, the hallmark features generally involve the skull, limbs, and genitalia, along with potential complications in various organ systems.

Symptoms

The clinical manifestations of Antley‑Bixler Syndrome are diverse and often involve multiple systems of the body (1). Some of the most common and defining symptoms include

- Craniosynostosis: Premature fusion of skull sutures, often leading to a misshapen head and increased intracranial pressure.

- Midface hypoplasia: Underdevelopment of the central facial bones, resulting in a flat or sunken appearance.

- Radiohumeral synostosis: Abnormal fusion of the radius and humerus bones in the arm, severely restricting elbow movement.

- Joint contractures: Limited range of motion in joints due to abnormal muscle or tendon development (2).

- Femoral bowing: Curvature of the thigh bone, which may cause walking difficulties.

- Genital anomalies: Ambiguous genitalia or underdeveloped reproductive organs, particularly in individuals with mutations affecting steroid metabolism.

- Hydrocephalus: Accumulation of fluid in the brain, which can lead to increased pressure and neurological symptoms.

- Choanal atresia or stenosis: Blockage or narrowing of the nasal passages, which can cause breathing difficulties, particularly in infants.

- Developmental delay and intellectual disabilities: Although not present in all cases, some children with ABS may experience cognitive or developmental challenges.

Each individual with ABS may present with a unique combination and severity of symptoms, making personalized care and multidisciplinary management crucial.

Causes

Antley‑Bixler Syndrome can arise from mutations in two distinct genes (2).

- FGFR2 (Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2): Mutations in this gene are associated with many craniosynostosis syndromes. FGFR2 mutations lead to abnormal signaling in bone development pathways, particularly affecting skull and limb formation.

- POR (Cytochrome P450 Oxidoreductase): Mutations in this gene disrupt steroid biosynthesis and electron transfer to cytochrome P450 enzymes. This form of ABS is sometimes called “Antley‑Bixler Syndrome with genital anomalies and disordered steroidogenesis.”

In some cases, ABS may occur sporadically due to new (de novo) mutations without any family history, while others may be inherited in an autosomal recessive or dominant pattern depending on the gene involved (1).

Risk Factors

Since Antley‑Bixler Syndrome is primarily genetic, the main risk factors include

- Family history of ABS or related genetic conditions (2).

- Consanguinity (parental relatedness), which increases the likelihood of inheriting autosomal recessive mutations.

- Carrier status of mutations in the FGFR2 or POR genes, which can be identified through genetic testing.

In most cases, there are no environmental triggers or maternal behaviors that cause ABS, though prenatal exposures are still under study in genetic syndromes in general.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing Antley‑Bixler Syndrome typically involves a combination of clinical assessment, imaging, and genetic testing (3).

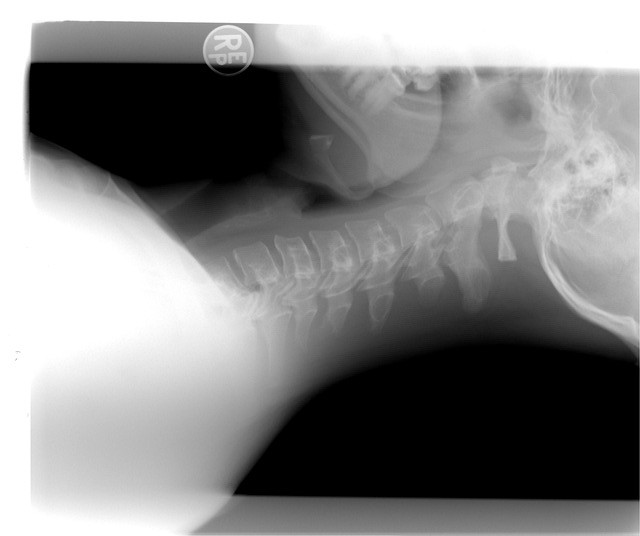

- Physical Examination: Noting physical abnormalities such as craniosynostosis, limb deformities, and genital anomalies.

- Imaging Studies: X-rays and CT scans can reveal bone fusions, skull shape, and internal abnormalities.

- MRI or Ultrasound: To detect soft tissue issues, organ development, or hydrocephalus.

- Genetic Testing: Confirmatory testing for mutations in FGFR2 or POR genes through blood samples.

- Hormonal and Metabolic Testing: Particularly important in cases involving POR mutations to identify endocrine dysfunctions.

Early diagnosis is essential to plan for potential surgical interventions, hormonal therapies, and developmental support (1).

Treatment Options

Treatment for Antley‑Bixler Syndrome is highly individualized and usually requires a multidisciplinary team (2). There is no cure, but several supportive treatments can improve quality of life and functionality

- Surgical Interventions

- Cranial surgery to relieve intracranial pressure and correct skull shape.

- Orthopedic surgery to address joint contractures or bone malformations like femoral bowing or synostosis.

- Reconstructive surgery for facial or genital anomalies.

- Endocrinological Treatment

- Hormone replacement therapy in cases with steroidogenesis defects.

- Monitoring of adrenal and sex hormone levels to guide treatment.

- Respiratory Support

- Surgery or intervention for choanal atresia.

- Tracheostomy may be required in severe cases of airway obstruction.

- Developmental and Supportive Therapies

- Physical therapy to improve joint mobility.

- Speech and occupational therapy for developmental delays.

- Educational support for learning disabilities, if present.

- Regular Monitoring: Children with ABS require close monitoring for growth, hormone levels, and neurological development.

Living With or Prevention

Living With ABS involves comprehensive, lifelong care and monitoring. The severity of the syndrome varies greatly, so while some individuals may live relatively normal lives with supportive treatment, others may have significant physical or intellectual challenges. Parents and caregivers often benefit from genetic counseling and psychosocial support (3).

Preventive Measures are limited due to the genetic nature of the syndrome, but the following can be considered:

- Genetic Counseling: For families with a history of ABS or known carrier status, counseling helps assess risks in future pregnancies (2).

- Prenatal Genetic Testing: In families at risk, testing via amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling may help detect mutations during pregnancy.

- In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) with Genetic Screening: For parents known to carry mutations, IVF combined with preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) can help avoid passing the condition to offspring (3).

References

- Escobar LF, Bixler D, Sadove M, Bull MJ. Antley-Bixler syndrome from a prognostic perspective: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet. 1988 Apr;29(4):829-36. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320290412. PMID: 3041834.

- McGlaughlin KL, Witherow H, Dunaway DJ, David DJ, Anderson PJ. Spectrum of Antley-Bixler syndrome. J Craniofac Surg. 2010 Sep;21(5):1560-4. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181ec6afe. PMID: 20818252.

- Kitoh H, Nogami H, Oki T, Arao K, Nagasaka M, Tanaka Y. Antley-Bixler syndrome: a disorder characterized by congenital synostosis of the elbow joint and the cranial suture. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996 Mar-Apr;16(2):243-6. doi: 10.1097/00004694-199603000-00021. PMID: 8742293.