Kniest dysplasia is a rare genetic disorder that affects the development of cartilage and bone, primarily impacting the skeletal system. It belongs to a group of disorders known as type II collagenopathies, caused by mutations affecting the type II collagen gene (1). This condition leads to short stature and various skeletal abnormalities, often identified in infancy or early childhood. Named after Dr. Wilhelm Kniest, who first described it in the 1950s, Kniest dysplasia presents a wide spectrum of physical manifestations. Though the condition does not typically affect intellectual development, individuals often experience lifelong orthopedic challenges (2). Understanding the nature of Kniest dysplasia is essential for timely diagnosis, supportive treatment, and improving the quality of life for those affected.

Symptoms

The symptoms of Kniest dysplasia vary in severity but generally become apparent during infancy or early childhood. The hallmark features of this disorder include (2):

- Short-trunk dwarfism: Individuals typically have short stature with a particularly shortened torso.

- Flattened facial features: This includes a flat nasal bridge and midface hypoplasia.

- Cleft palate: Some individuals are born with a cleft palate, which can interfere with feeding and speech (2).

- Joint stiffness or hypermobility: Joint abnormalities can range from unusually flexible to extremely stiff joints (3).

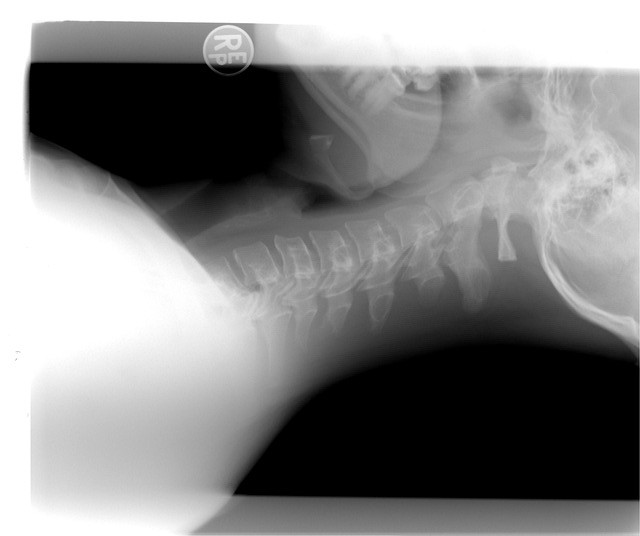

- Kyphoscoliosis: Abnormal curvature of the spine, such as scoliosis (sideways) and kyphosis (forward rounding), may develop.

- Hearing and vision problems: Sensorineural hearing loss and severe nearsightedness (myopia) are common due to abnormalities in the eyes and ears.

- Enlarged joints and metaphyseal flaring: The ends of long bones may appear flared and enlarged on X-rays.

- Respiratory complications: Chest deformities can lead to breathing difficulties in severe cases.

These symptoms can impact mobility and day-to-day functioning, often necessitating long-term orthopedic care and supportive therapies (2).

Causes

Kniest dysplasia is caused by mutations in the COL2A1 gene, which encodes type II collagena protein essential for the normal development of cartilage and the vitreous humor of the eye. Type II collagen is a vital component of connective tissues in joints and cartilage. When mutations occur, it results in abnormal or insufficient collagen production, leading to improper cartilage formation and skeletal abnormalities (3).

This condition follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, meaning that only one copy of the mutated gene from either parent is sufficient to cause the disorder. In many cases, however, the mutation arises spontaneously (de novo), with no family history of the condition (3).

Risk Factors

As a genetic disorder, Kniest dysplasia is not influenced by lifestyle or environmental factors. However, several risk factors can increase the likelihood of a child being born with this condition (3):

- Family history: Individuals with a parent who has Kniest dysplasia have a 50% chance of passing it on to their children.

- New genetic mutations: Even without a family history, spontaneous mutations during conception can result in the condition.

- Advanced paternal age: Some studies suggest a higher risk of new mutations in offspring from older fathers, although this is still under research.

Because the condition is rare, exact incidence rates are not well documented, and most cases are identified through individual clinical evaluations (2).

Diagnosis

Diagnosing Kniest dysplasia typically involves a combination of clinical assessments, imaging, and genetic testing:

- Physical examination: A pediatrician may notice physical signs such as short stature, facial features, or joint abnormalities during infancy.

- Radiographic imaging (X-rays): Skeletal surveys often reveal characteristic signs like dumbbell-shaped long bones, flattened vertebrae (platyspondyly), and metaphyseal flaring (2).

- Genetic testing: A definitive diagnosis can be made by identifying mutations in the COL2A1 gene through molecular testing (1).

- MRI or CT scans: These may be used to assess the extent of spinal or joint abnormalities.

- Audiological and ophthalmological evaluations: Due to the common occurrence of hearing and vision issues, these specialized assessments help in early detection and management.

Early diagnosis is essential for beginning supportive therapies that can improve outcomes and prevent complications.

Treatment Options

There is no cure for Kniest dysplasia, but treatment focuses on managing symptoms and improving the individual’s quality of life. A multidisciplinary team approach is usually required, involving pediatricians, orthopedic surgeons, physical therapists, audiologists, and ophthalmologists. Treatment options may include (2):

- Orthopedic interventions:

- Surgical correction: Procedures may be needed to correct spinal deformities, joint contractures, or cleft palate.

- Joint stabilization: Surgeries can be performed to increase mobility or reduce pain in affected joints.

- Physical therapy: Regular exercises help improve strength, flexibility, and coordination.

- Hearing aids and vision correction: Devices and corrective lenses can manage hearing loss and myopia effectively.

- Assistive devices: Wheelchairs, braces, or walkers may be necessary depending on mobility limitations.

- Pain management: Medications and lifestyle adjustments can help manage chronic pain, especially in joints and the spine.

While some orthopedic complications may require multiple surgeries over a lifetime, early intervention can significantly improve mobility and function.

Living With or Prevention

Living With Kniest Dysplasia

Living with Kniest dysplasia involves adapting to physical limitations and seeking ongoing medical support. While intellectual development is typically unaffected, the physical challenges can impact schooling, social interactions, and independence. With the right support:

- Educational support services can help address hearing or speech impairments.

- Psychosocial counseling may be beneficial for coping with social stigma or emotional difficulties.

- Community support groups can connect families with others facing similar challenges, offering mutual guidance and reassurance.

Many individuals with Kniest dysplasia go on to lead fulfilling lives, participate in school and work, and enjoy active social lives with the proper accommodations and care.

Prevention

Since Kniest dysplasia is genetic, prevention is not possible in the traditional sense (3). However:

- Genetic counseling is crucial for families with a history of the condition who are considering having children.

- Prenatal testing and preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) can detect the disorder during pregnancy or before implantation in IVF procedures, allowing families to make informed decisions.

While these options are not universally accessible, they offer a preventive route for those at known risk.

References

- Bogaert R, Wilkin D, Wilcox WR, Lachman R, Rimoin D, Cohn DH, Eyre DR. Expression, in cartilage, of a 7-amino-acid deletion in type II collagen from two unrelated individuals with Kniest dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 1994 Dec;55(6):1128-36. PMID: 7977371; PMCID: PMC1918451.

- Hicks J, De Jong A, Barrish J, Zhu SH, Popek E. Tracheomalacia in a neonate with kniest dysplasia: histopathologic and ultrastructural features. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2001 Jan-Feb;25(1):79-83. doi: 10.1080/019131201300004726. PMID: 11297324.

- Spranger J, Winterpacht A, Zabel B. The type II collagenopathies: a spectrum of chondrodysplasias. Eur J Pediatr. 1994 Feb;153(2):56-65. doi: 10.1007/BF01959208. PMID: 8157027.