Dissecting osteitis, also known as Osteitis Dissecans, is a rare but significant orthopedic condition characterized by localized bone and cartilage death due to disrupted blood supply (1). Most commonly affecting the knee, elbow, or ankle joints, it typically arises in adolescents and young adults who are physically active. The condition can range from mild to severe, depending on the extent of bone and cartilage damage, and may eventually lead to the separation of a bone fragment that can float freely within the joint. Understanding the clinical features, etiology, and treatment options is vital for early diagnosis and management, which can significantly affect long-term outcomes.

Symptoms

The symptoms of dissecting osteitis can vary depending on the severity and the joint affected. In its early stages, the condition may be asymptomatic or only mildly uncomfortable. As it progresses, common signs and symptoms include (1):

- Joint Pain: Usually worsens with activity and improves with rest.

- Swelling: Particularly after intense physical activity.

- Stiffness or Reduced Range of Motion: Especially in the affected joint.

- Clicking or Locking Sensation: Due to loose bone fragments within the joint.

- Joint Instability: In advanced cases where the cartilage and bone have completely detached.

The symptoms typically worsen over time if left untreated, eventually interfering with daily activities and sports participation (1).

Causes

The exact cause of dissecting osteitis is not definitively understood, but it is believed to involve a combination of mechanical, vascular, and genetic factors. Potential causes include (2):

- Repetitive Trauma or Microtrauma: Continuous stress on a joint, such as from sports, may impair blood supply to a small area of bone.

- Ischemia (Reduced Blood Flow): Disruption of vascular supply to subchondral bone leads to necrosis (bone death).

- Genetic Predisposition: Some individuals may have an inherited vulnerability to bone and cartilage problems.

- Abnormal Bone Development: In adolescents, areas of the bone that are still developing may be more susceptible to damage.

Risk Factors

Several risk factors increase the likelihood of developing dissecting osteitis, including (1):

- Age and Growth Stage: Most common in adolescents aged 10–20 years, particularly those undergoing rapid growth spurts.

- High-impact Sports: Athletes involved in activities like football, basketball, gymnastics, or track are at higher risk due to repetitive joint stress.

- Gender: Males are more frequently affected, although awareness and diagnosis in females are increasing.

- Genetic History: A family history of joint conditions or osteochondral disorders may increase susceptibility.

- Joint Abnormalities: Congenital or developmental joint conditions may predispose individuals to osteitis.

Diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis of dissecting osteitis requires a combination of clinical evaluation and imaging studies. The diagnostic process typically involves (3):

- Medical History and Physical Exam: Evaluation of pain, swelling, range of motion, and joint stability.

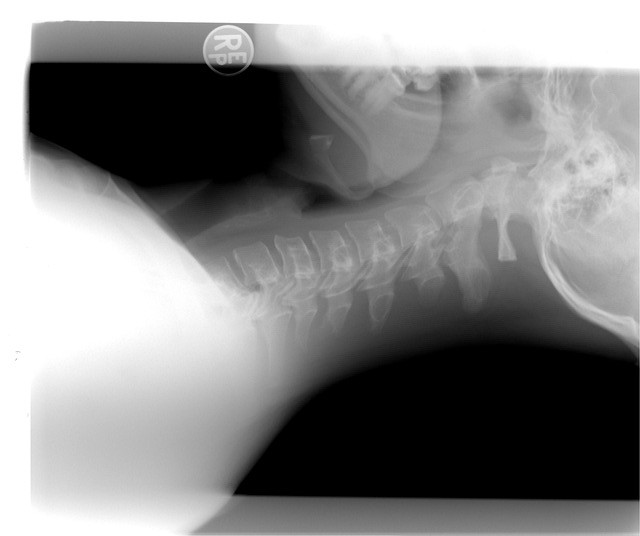

- X-rays: Initial imaging modality that may show bone lesions or fragmentation.

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): Offers detailed images of cartilage and bone and can detect early changes in blood flow.

- CT Scans (Computed Tomography): Provide precise images of bone structure and are helpful in surgical planning.

- Arthroscopy: In some cases, a minimally invasive procedure may be used to directly visualize the inside of the joint and assess the extent of damage.

MRI is considered the gold standard for early diagnosis and staging of the condition.

Treatment Options

Treatment of dissecting osteitis depends on factors such as the patient’s age, activity level, the severity of the lesion, and whether the bone fragment is still attached (1). Treatment modalities are divided into non-surgical and surgical approaches:

Non-Surgical Management

- Rest and Activity Modification: Avoiding high-impact activities to reduce joint stress.

- Physical Therapy: Exercises to maintain joint mobility and strengthen surrounding muscles.

- Bracing or Immobilization: May help stabilize the joint and promote healing.

- Pain Management: NSAIDs (Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) to reduce inflammation and discomfort.

Non-surgical treatment is more successful in skeletally immature individuals (i.e., children and adolescents) with stable lesions (1).

Surgical Management

Surgical intervention is considered when conservative treatment fails or the lesion is unstable. Common procedures include:

- Drilling or Microfracture Surgery: Stimulates blood supply to the area to promote healing.

- Fixation of Detached Fragments: Screws or pins may be used to reattach loose bone fragments.

- Osteochondral Grafting: Healthy bone and cartilage are transplanted from another part of the joint or a donor source.

- Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI): A two-step procedure where a patient’s cartilage cells are grown and re-implanted.

Post-surgical rehabilitation is critical for regaining strength, range of motion, and function.

Living With or Prevention

Living with Dissecting Osteitis involves adapting to lifestyle changes and undergoing rehabilitation, particularly for those who have had surgery. Regular follow-ups with an orthopedic specialist, adherence to physical therapy, and avoiding high-impact activities until full recovery are essential for optimal outcomes (2).

Prevention of dissecting osteitis isn’t always possible, especially when related to genetic or vascular factors. However, risk can be minimized by:

- Avoiding repetitive joint stress in young athletes.

- Encouraging proper technique and conditioning in sports.

- Promptly addressing joint injuries or persistent pain in children and adolescents.

- Educating athletes, parents, and coaches about early symptoms.

Early diagnosis and intervention are key to preventing long-term joint damage and arthritis.

References

- Andriolo L, Crawford DC, Reale D, Zaffagnini S, Candrian C, Cavicchioli A, Filardo G. Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee: Etiology and Pathogenetic Mechanisms. A Systematic Review. Cartilage. 2020 Jul;11(3):273-290. doi: 10.1177/1947603518786557. Epub 2018 Jul 12. PMID: 29998741; PMCID: PMC7298596.

- Kirsch JM, Thomas J, Bedi A, Lawton JN. Current Concepts: Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Capitellum and the Role of Osteochondral Autograft Transplantation. Hand (N Y). 2016 Dec;11(4):396-402. doi: 10.1177/1558944716643293. Epub 2016 Aug 24. PMID: 28149204; PMCID: PMC5256660.

- Gomella P, Mufarrij P. Osteitis pubis: A rare cause of suprapubic pain. Rev Urol. 2017;19(3):156-163. doi: 10.3909/riu0767. PMID: 29302238; PMCID: PMC5737342.