Apert syndrome is a rare genetic disorder characterized by the premature fusion of certain skull bones, a condition known as craniosynostosis. This early fusion affects the shape of the head and face. Additionally, individuals with Apert syndrome often have webbed or fused fingers and toes, a condition called syndactyly. First described by French physician Eugène Apert in 1906, this congenital condition affects approximately 1 in 65,000 to 88,000 newborns worldwide. Apert syndrome is a part of a broader group of craniosynostosis syndromes, including Crouzon and Pfeiffer syndromes, but it is distinct due to the combination of facial anomalies and limb abnormalities (1).

Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of Apert syndrome vary in severity but typically include (1):

- Craniosynostosis: Early closure of the skull sutures leads to a cone-shaped or tower-shaped head (acrocephaly).

- Facial Abnormalities: Midface hypoplasia (underdevelopment of the midfacial bones), a prominent forehead, wide-set eyes (hypertelorism), and a beaked nose are common.

- Syndactyly: Fusion of fingers and toes, often involving both soft tissue and bone, resulting in “mitten-like” hands or feet.

- Dental Issues: Crowded teeth, delayed tooth eruption, and malocclusion.

- Intellectual Development: Varying levels of cognitive impairment, though many children have normal intelligence (2).

- Hearing and Vision Problems: Due to structural abnormalities of the ears and eyes.

- Respiratory Difficulties: Narrow nasal passages can lead to breathing issues and sleep apnea.

Additional features may include skin conditions such as acne, fused cervical vertebrae, and, in some cases, congenital heart defects or gastrointestinal anomalies.

Causes

Apert syndrome is caused by mutations in the FGFR2 (fibroblast growth factor receptor 2) gene, which plays a crucial role in bone development and maintenance (1). This mutation leads to excessive signaling, causing bones to fuse too early in development (3).

Nearly all cases of Apert syndrome are due to de novo (new) mutations, meaning they occur spontaneously and are not inherited from the parents. However, the condition follows an autosomal dominant pattern, so an affected individual has a 50% chance of passing the condition on to their offspring.

Risk Factors

While Apert syndrome is mostly caused by new mutations, certain factors increase the risk (2):

- Advanced Paternal Age: The risk of new FGFR2 mutations increases with the father’s age, especially beyond the age of 35.

- Family History: Although rare, if one parent has Apert syndrome, there is a significant chance of transmission to their child (3).

- Genetic Mutations: Specific point mutations in the FGFR2 gene, particularly in certain nucleotide positions, are associated with Apert syndrome.

Environmental or lifestyle-related risk factors have not been linked to the development of this condition.

Diagnosis

Apert syndrome can often be diagnosed shortly after birth based on the physical signs. However, a complete diagnostic process typically includes (4):

- Clinical Examination: Observation of craniofacial features and limb abnormalities by a geneticist or pediatric specialist.

- Genetic Testing: Molecular testing for FGFR2 mutations confirms the diagnosis.

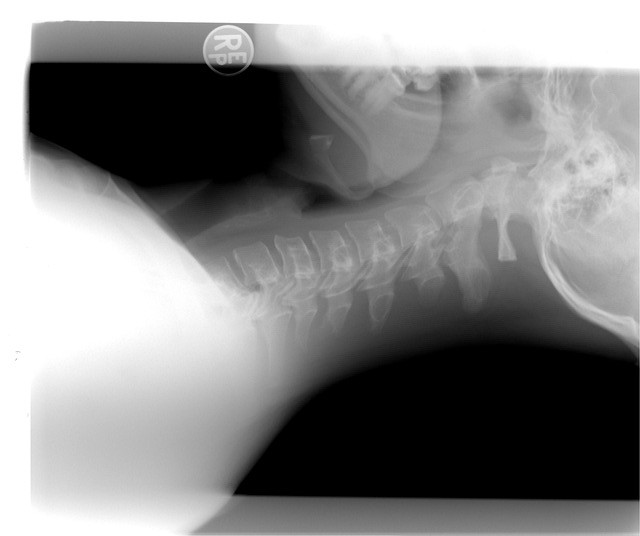

- Imaging Studies:

-

- X-rays and CT Scans: To assess the extent of craniosynostosis and syndactyly (1).

- MRI: May be used to evaluate brain structure if neurological symptoms are present.

- Prenatal Diagnosis: In some cases, prenatal ultrasounds may detect craniosynostosis or fused digits. Further confirmation is possible through amniocentesis and genetic analysis.

Early diagnosis is critical for planning appropriate interventions and management strategies (2).

Treatment Options

Treatment for Apert syndrome is multidisciplinary, aiming to address both functional and aesthetic issues. Management usually includes (3):

- Surgical Interventions:

-

- Cranial Surgery: Performed during infancy (usually before 1 year of age) to relieve intracranial pressure and correct skull shape.

- Midface Advancement Surgery: Done in childhood or adolescence to improve breathing, vision, and facial appearance.

- Syndactyly Release Surgery: Typically done in stages during early childhood to improve hand and foot function.

- Orthodontic and Dental Care: Management of dental malocclusion, palate issues, and overcrowded teeth (1).

- Hearing and Vision Support:

-

- Hearing aids or ear surgeries for conductive hearing loss.

- Glasses or corrective surgeries for strabismus or other vision problems.

- Speech and Developmental Therapy: To support language development and address cognitive delays.

- Psychological Support: Counseling and support groups help children and their families cope with the social and emotional challenges of the condition.

Ongoing care and monitoring by a craniofacial team (which includes neurosurgeons, plastic surgeons, ENT specialists, and developmental therapists) is essential throughout the patient’s life (4).

Living With or Prevention

Living with Apert syndrome requires ongoing medical attention, but many individuals lead fulfilling lives. Key considerations include (2):

- Early Interventions: Early surgeries and therapies significantly improve quality of life and functional outcomes.

- Educational Support: Some children may benefit from individualized education plans (IEPs) tailored to their cognitive and physical needs.

- Social Integration: Promoting inclusion and self-esteem through peer support and public awareness can help mitigate social stigma.

- Regular Monitoring: Lifelong monitoring is often necessary to address evolving issues, especially during periods of rapid growth.

Prevention of Apert syndrome is not generally possible since it results from spontaneous genetic mutations. However, genetic counseling can be offered to prospective parents with a family history or who are known carriers of the mutation (4).

References

- Koca TT. Apert syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. North Clin Istanb. 2016 May 14;3(2):135-139. doi: 10.14744/nci.2015.30602. PMID: 28058401; PMCID: PMC5206464.

- Singh N, Verma P, Bains R, Mutalikdesai J. Apert syndrome: craniofacial challenges and clinical implications. BMJ Case Rep. 2024 Jul 16;17(7):e260724. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2024-260724. PMID: 39013624.

- Karsonovich T, Patel BC. Apert Syndrome. 2025 Apr 12. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. PMID: 30085535.

- Wenger TL, Hing AV, Evans KN. Apert Syndrome. 2019 May 30. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2025. PMID: 31145570.